by Dierk Günther

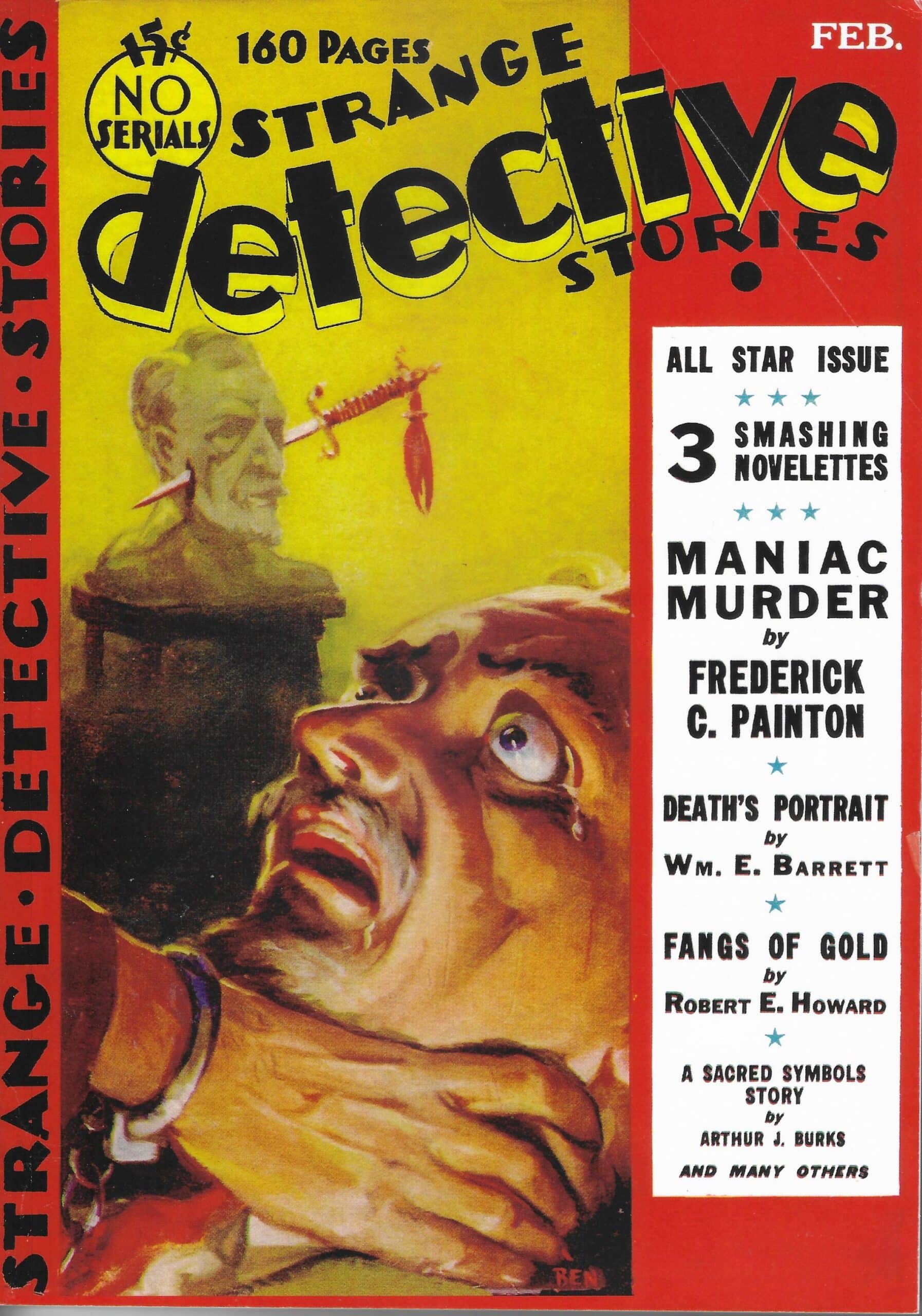

Between December 1933 and June 1936, a group of rather unusual Robert E. Howard stories were published: “Black Talons” (1933), “The Tomb’s Secret” (1934), “Fangs of Gold” (1934), “Names in the Black Book” (1934), “Graveyard Rats” (1936) and “Black Wind Blowing” (1936) were published in the magazines Strange Detective Stories, Super Detective Stories and Thrilling Mystery, which specialized in crime and detective stories.

These stories hold a special place in Howard’s work. Although they were published in magazines catering to the crime and detective markets, they were definitely not typical with their heavy Robert E. Howard spin. Moreover, Robert E. Howard’s personal opinion about his achievement in this genre is also highly noteworthy. In May 1936 he wrote to H. P. Lovecraft:

“I have definitely abandoned the detective field, where I never had any success anyway, and which represents a type of story I actively detest. I can scarcely endure to read one, much less write one.”

– (Means to Freedom Vol. 2, 953)

This statement raises several questions: Why would Howard write anything in a genre he admitted to not only hating, but also not having a propensity for? Are Howard’s crime/detective stories actually ‘crime’ stories in the way literary dictionaries define it? And if not, what are the differences? And lastly, are these stories really as bad as Howard regarded them?

(1) Howard’s Possible Reasons for Writing Detective/Crime Stories.

For Howard, who wanted to make a living as a professional writer, the decision to try getting out of fantasy in favor of other genres and markets was not simply a logical one, but one based on painful necessity. He was without any doubt versatile enough and had the necessary skills to be successful outside of fantastic fiction. A look at his work in genres such as horror, historical short stories about the crusaders, (weird) western tales, boxing stories, and even his work published in the Spicy magazines clearly demonstrates that Howard could write and deliver quality in a variety of environments.

Unfortunately, one can only speculate as to the reasons why Howard wrote in a genre, which he admitted to “actively detest.” By the time Howard began to write detective stories, the market was already dominated by stars like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Furthermore, the magazines selling crime stories had a sufficient stock of experienced crime storywriters available, writers who specialized in catering to the needs of their customers. All of this made the attempts of latecomers trying to enter this market a daunting task.

Getting a foot into the crime stories market through a method Howard was an expert in –mixing different genres – also didn’t seem to be an option. For Howard, that mix would be fantasy and horror, genres he had sufficient experience writing in. The result of such a mixture though, would have probably created another supernatural sleuth, and that throne was already firmly held by Seabury Quinn and his Jules Grandin series.

There is a high possibility that Howard’s literary agent Otis Adelbert Kline encouraged him to write detective stories. In a letter to Lovecraft, dated September 1933, Howard mentions that “Kline has been a big help in teaching me the technique of detective story writing” (Howard and Lovecraft Vol. 2, 634). This though is not sufficient proof that Kline was really involved in Howard’s decision to write crime stories.

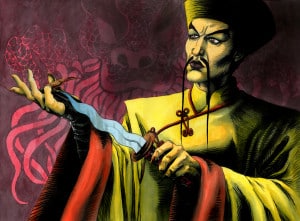

Another possibility of why Howard might have felt confident in writing crime stories was his love of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories. According to Howard’s personal library inventory list, he possessed eight books by Sax Rohmer. Howard also wrote parodies of Fu Manchu stories (‘Few Menchu’ or ‘Fooey Mancucu’) (Collected Letters 1, 53-55, 139 – 142, 113 – 119), which he sent to his friend Tevis Clyde Smith (March 1925/October 1927/February 1929). This clearly indicates that Howard was very familiar with the stories about the Chinese villain. The influence of these Fu Manchu stories on Howard was so strong that some of Howard’s crime stories feature a Mongolian super-villain by the name of Erlik Khan that was obviously based on Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu.

Another possibility of why Howard might have felt confident in writing crime stories was his love of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories. According to Howard’s personal library inventory list, he possessed eight books by Sax Rohmer. Howard also wrote parodies of Fu Manchu stories (‘Few Menchu’ or ‘Fooey Mancucu’) (Collected Letters 1, 53-55, 139 – 142, 113 – 119), which he sent to his friend Tevis Clyde Smith (March 1925/October 1927/February 1929). This clearly indicates that Howard was very familiar with the stories about the Chinese villain. The influence of these Fu Manchu stories on Howard was so strong that some of Howard’s crime stories feature a Mongolian super-villain by the name of Erlik Khan that was obviously based on Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu.

(2) Howard’s Brand of Crime Stories

In the Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, crime fiction is defined as “the commission and detection of crime, with the motives, actions, arraignment, judgment, and punishment of a criminal is one of the greatest paradigms of narrative. Textualized theft, assault, rape and murder begin with the earliest epics, and are central to Classical and much subsequent tragedy.” (192)

Although it is widely assumed that the publication of E. A. Poe’s “Murder in the Rue Morgue” (1841) marked the origin of the crime fiction genre, this is actually not the case. According to the Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory the first crime story can be traced back to the late 18th century to William Godwin’s Caleb Williams (1794). This new genre culminated in its first phase with the 1887 publication of Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story, which established the short story as the genre’s prominent form (a form also used by Howard).

The Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory sets the end of this First Golden Age of Detection in 1914. A Second Golden Age of crime fiction began in the late 1920s when female writers such as Agatha Christie successfully entered the stage. These women extended the short story to full novel length. In the United States crime fiction became popular via the pulp fiction market, where according to Ron Goulart, “the private eye was born in the early 1920s and flourished in the decades between the two World Wars” (Cheap Thrills, 89) with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler to be the most prominent writers in the field.

There seems to be direct opposition between the British Golden Age crime novels and those from the American hard-boiled school. British crime fiction in the vein of Agatha Christie is described as:

‘The classic Golden Age novels are hermetically sealed, typically by location in a country house (though any isolated setting will do), and structurally consist of a discovery (the body), a sequence of red herrings (a parade of suspects), and a denouement (the detective announces whodunit)’

– (Dictionary 194)

One point of criticism of these British novels with their amateur detectives was the omitting of professional police crime investigations. This omission turned these novels into surrealistic artificial constructions. (Dictionary 194)

A reaction to this British school of crime stories was American crime noir with their stark and violent stories, usually placed in grimy urban settings, featuring both lone but professional investigators and police. These tales also tended to blur the moral distinctions between criminals and agents of law enforcement. (194)

Howard’s ability to write crime stories can be discovered in a rather unexpected time period: the early stories in the Conan of Cimmeria series contain many elements of a typical crime story, even some characteristics of the hardboiled genre would eventually find their way into Howard’s crime stories. “The God in the Bowl” and “The Tower of the Elephant” are two perfect examples.

“The God in the Bowl,” which is the third story in the Conan series has actually all the ingredients of a whodunit crime story: A mysterious murder in a secluded location, several suspects, a ‘Hyborian Age proto cop’ and a morally ambiguous protagonist. “The Tower of the Elephant” starts out as the story of two thieves who try to burglar a mysterious tower that no other thief has ever dared to attempt.

“The God in the Bowl,” which is the third story in the Conan series has actually all the ingredients of a whodunit crime story: A mysterious murder in a secluded location, several suspects, a ‘Hyborian Age proto cop’ and a morally ambiguous protagonist. “The Tower of the Elephant” starts out as the story of two thieves who try to burglar a mysterious tower that no other thief has ever dared to attempt.

It is hard to imagine that Robert E. Howard, whose stories’ trademarks are fast-paced action scenes, could have written crime stories in the vein of the British school, featuring refined and restrained amateur gentlemen detectives who solve their cases with passive observation and the calm accumulation of clues. When it came to writing crime, the American hard-boiled school with its violent action and morally ambiguous characters would seem to be a perfect fit for Howard.

A look at Howard’s crime/detective stories that were published during his lifetime demonstrate that they do indeed favor action and thrills over detailed descriptions of investigative strategies such as can be found in Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op series.

In “Black Talons,” an African cult takes revenge for having been robbed of its gold. The story’s whodunit-plot is extremely constructed. The plot moves forward not through the gathering of evidence or the eliminating of possible suspects, but through events like abductions and killings. Other features of the story include its intense atmosphere, and the graphic descriptions of killings and threats of torture. These characteristics also make it possible to categorize ‘Black Talons’ as a horror story.

“Fangs of Gold” (also titled “People of the Serpent“) features detective Steve Harrison who hunts a Chinese criminal hiding in the swamps. This setting is an unexpected departure from a genre that usually takes place in a city. This hunt then turns into a confrontation with the leader of a Voodoo cult, reminiscent of Howard’s infamous “Black Canaan.” Once again the story is not so much about investigating a crime by gathering evidence, as it is an excuse for fast paced action.

In “The Tomb’s Secret” (or “Teeth of Doom“) and “Names in the Black Book,” Howard takes a different approach highlighting the possible influence of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories. However, this time the villains are not African cults, but a Mongolian secret society known by the name of Sons of Erlik. “The Tomb’s Secret” suffers from a highly constructed plot. Its saving merits are a tense atmosphere and a well-written action scene that unfolds in a ‘lonely house on the outskirt of the city.’ The detective featured in this story does not really investigate the case, but merely points out obvious facts. The story’s final twist reveals that a third player has manipulated the story’s protagonist. Considering the revelations at the end of “The Tomb’s Secret,” the story would better qualify as a secret agent thriller than a standard crime story.

In “The Tomb’s Secret” (or “Teeth of Doom“) and “Names in the Black Book,” Howard takes a different approach highlighting the possible influence of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories. However, this time the villains are not African cults, but a Mongolian secret society known by the name of Sons of Erlik. “The Tomb’s Secret” suffers from a highly constructed plot. Its saving merits are a tense atmosphere and a well-written action scene that unfolds in a ‘lonely house on the outskirt of the city.’ The detective featured in this story does not really investigate the case, but merely points out obvious facts. The story’s final twist reveals that a third player has manipulated the story’s protagonist. Considering the revelations at the end of “The Tomb’s Secret,” the story would better qualify as a secret agent thriller than a standard crime story.

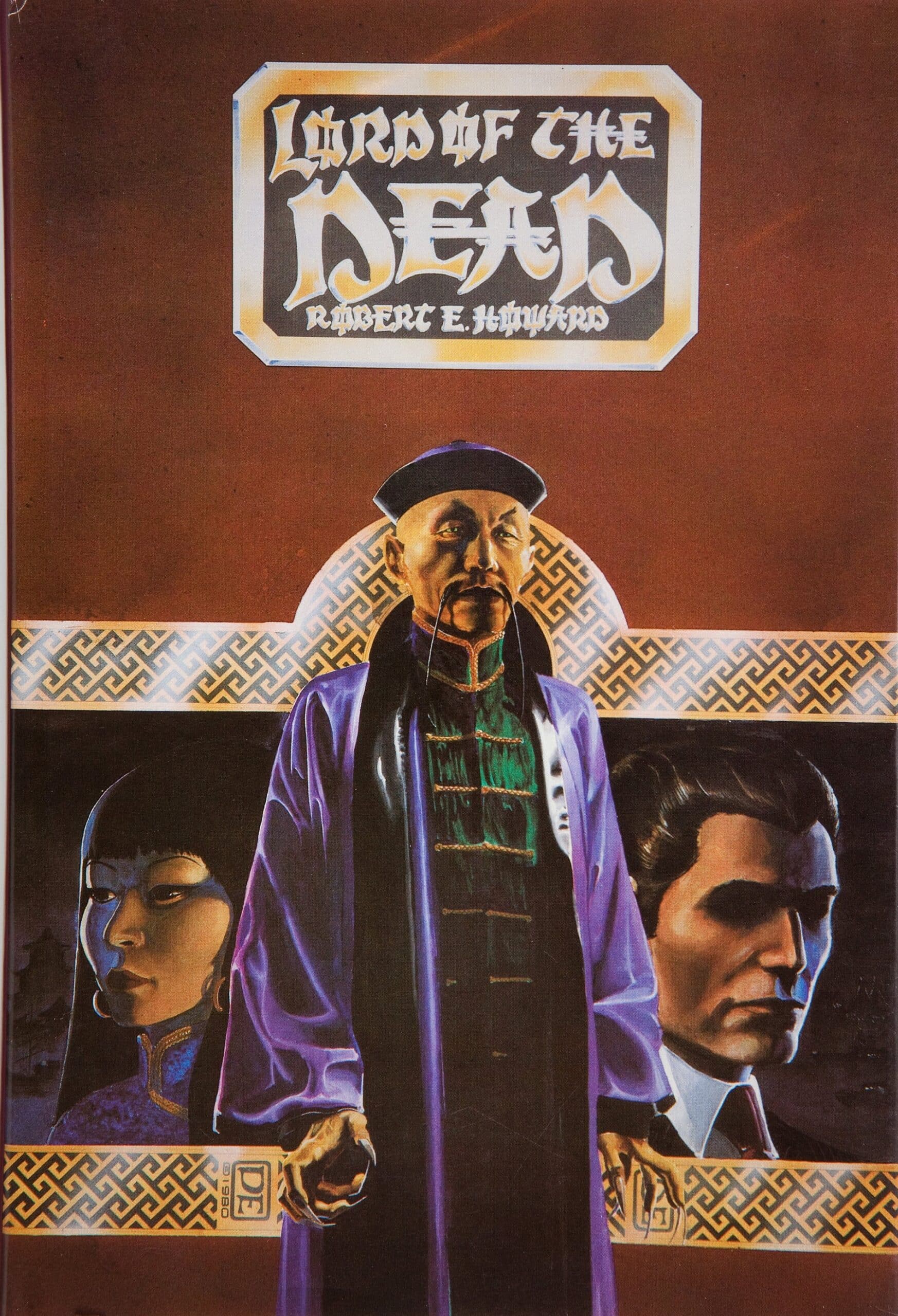

“Names in the Black Book,” the sequel to the unpublished story “Lord of the Dead,” features the Fu Manchu influenced Mongolian villain Erlik Khan, whom the protagonist had seemingly defeated in “Lord of the Dead.” In spite of the main character being a private detective, and its urban setting in the Chinese quarter on River Street, the story can hardly be defined as a crime story. It is more accurately defined as an action story in which the survivors of “Lord of the Dead” try to avoid the revenge of Erlik Khan. What makes this story interesting is an action scene in which the main characters have barricaded themselves in a building under attack from Erlik Khan’s faceless minions. This is a scenario reminiscent of John Carpenter’s 1976 movie Assault on Precinct 13 where a group of people in a shuttered police station is under siege by gang members.

“Graveyard Rats” and “Black Wind Blowing,” published in 1936 in the Thrilling Mystery magazine, feature such villains as a madman and a Satanist cult offering human sacrifices. Both stories lean more in the direction of horror than crime. What makes these otherwise forgettable stories nonetheless interesting is their setting in 20th century rural Texas. Howard had already written several (weird) western stories set in his native Texas and had indicated in letters to H. P. Lovecraft and August Derleth that he was considering leaving the fantastic field in favor of westerns. In this context “Graveyard Rats” and “Black Wind Blowing” can also be regarded as a possible experiment of Howard’s, an attempt to see how much he could use his native region as a stage for crime.

When comparing Howard’s published and rather unconventional crime stories with those that were rejected (“Lord of the Dead“, “The Silver Heel“, “Black Moon“, “Voice of Death” and “House of Suspicion“), an interesting fact emerges: with the exception of ‘Lord of the Dead,’ all rejections actually fit well with the definition of ‘crime stories’ provided above. Every one of them stick to the formulistic genre plot structure that start with the detection of a mystery/crime, followed by a parade of red herrings (a.k.a. ‘possible suspects’) and finishes with the crime or mystery being solved or explained.

The problem with these stories is that the solutions are too contrived to be believable, for example a hidden record player used to drive a person into madness as featured in ‘The Voice of Death.’ A lack of action sequences is also not helpful in making already formulistic and overly constructed stories interesting.

The big exception among these rejections is “Lord of the Dead,” which was probably not accepted because it focused too much on action, especially in a way that was incompatible with a crime story. In one highly memorable scene, the protagonist detective Steve Harrison fights an army of enemies with an expertly wielded battle-axe.

This brings us to another special feature in Howard’s crime stories: The detectives and the private eyes.

This brings us to another special feature in Howard’s crime stories: The detectives and the private eyes.

The main characters in Howard’s stories of whatever genre were never passive, but always active, powerful forces. While a Mrs. Marple or a Hercule Poirot patiently gathered evidence piece by piece, finally luring a suspect into unintentionally admitting his/her crime, Howard’s detectives mostly gather their evidence by fighting one co-conspirator after another until they face-off with the ultimate perpetrator. This does not mean that Howard’s detectives were not also capable of solving a mystery with intellect. This strategy though can only be found in those stories that were rejected by Strange Detective Stories, Super Detective Stories and Thrilling Mystery magazine.

The detectives of the hard-boiled school of Chandler or Hammett are hard smoking and drinking tough men who are at times violent and always appreciative of the sight of a well-curved female body. The cities where they work are their territory, and they know their ways through the urban jungle. Hammett’s detectives in his Continental Op series know their good from their bad cops, as well as the good and bad crooks who provide them with the information necessary to solve their cases. There is one decisive point though that makes them different from Howard’s detectives:

Detectives Buckley, Steve Harrison and Brock Rollins1 of Howard’s stories, although working in cities – the manifestation of civilization – are far from being products of civilization, but rather barbarians in 20th century clothes. Brock Rollins, the protagonist of “The Tomb’s Secret” is described like this: “Brock Rollins bulked big in the dingy back-room appointed for the meeting. His massive shoulders and thick body dwarfed his height. His cold blue eyes contrasted with the thick black hair that crowned his low broad forehead, and his civilized garments could not conceal the almost savage muscularity of his hard frame”. (“The Tomb’s Secret” 355, Exotic Writings of Robert E. Howard)

Dashiell Hammet on the other hand describes his most famous character, Sam Spade, in quite a different manner. Despite the hint of physical strength, his appearance is otherwise far from threatening, unlike Howard’s detective Brock Rollins:

‘Samuel Spade’s jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller, v. His yellow-grey eyes were horizontal. The v motif was picked up again by thickish brows rising outward from twin creases above a hooked nose, and his pale brown hair grew down—from high flat temples—in a point on his forehead. He looked rather pleasantly like a blond Satan. (…)

Spade rose bowing and indicating with a thick-fingered hand the oaken armchair beside his desk. He was quite six feet tall. The steep rounded slope of his shoulders made his body seem almost conical—no broader than it was thick—and kept his freshly pressed grey coat from fitting very well.’

– (The Maltese Falcon)

This barbarism of Howard’s detectives is most evident in “Lord of the Dead.” Here detective Steve Harrison follows a suspect into the (literal) underworld of the city’s Chinese quarter, where he sheds his civilized 20th century self and changes into a savage barbarian. In the story’s climactic scene, that could have been written for a Kull or Conan story, Steve Harrison is facing the minions of the super-villain Erlik Khan. Bleeding, his clothes torn and with his back to the wall, the 20th century detective goes berserk and fights his enemies with a battle-axe. Although Lord of the Dead is superior to most of Howard’s published detective stories, featuring an exciting plot, a mysterious atmosphere, and a well-described urban setting in form of the Chinese quarter on River Street, the story was rejected, probably because of this atypical action scene.

Physical strength is a feature that Howard stresses in the description of all three detectives. Nonetheless this physical strength is actually of hardly any use to these men in their quest for crime solving. As has been pointed out, Howard’s detective stories certainly do not lack action. Most of the fights, however, are gunfights and not physical confrontations fought with bare hands or crude weapons. The strength of Howard’s detectives serves better to intimidate suspects into giving away their secrets than being actually used in physical confrontations.

Another notable point about the detectives in Howard’s crime stories is that when it comes to the decisive moment of solving the crime, they are actually not the ones who do it, but are mostly simple bystanders. In “The Tomb’s Secret” (or “Teeth of Doom“), the sequel to the unpublished “Lord of the Dead,” Brock Rollins realizes that he has just been played by the Chinese secret service to help them thwart the plot of a Mongolian villain.

Detective Buckley in ‘Black Talons’ does not only admit to having suspected the wrong person, but also happens to be around only by coincidence when the real perpetrator divulges himself by boasting about his crime.

And in “Fangs of Gold” (or “People of the Serpent“) it is not Steve Harrison who is preventing a possible uprising of African American inhabitants of a swamp, but a woman who Harrison happened to rescue during his primary mission of finding a Chinese criminal hiding there. It is also noteworthy that Harrison doesn’t even manage to bring the man out of the swamps alive. Having lost his handcuffs (!) and unintentionally having cut the ropes with which he had bound the suspect (!!), Harrison shoots the man when he, not surprisingly, attempts to escape.

One possible reason why Howard felt that he couldn’t get into writing hard-boiled crime stories was his personal background of living in a rural environment, which made it difficult, perhaps even impossible for him to convincingly describe an urban setting. (This on the other hand might have also been the reason that he later tried to set the stage of his crime stories in a more familiar setting – rural Texas). Howard was absolutely no hillbilly nor wholly unfamiliar with big cities, but unfortunately his experiences with big city life wouldn’t be sufficient enough to write convincingly of such places. He undertook trips to San Antonio, but the San Antonio culture full of Texas history was vastly different from the setting of urban jungles like Los Angeles, Hollywood, New York or San Francisco that were featured in the stories of Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett.

The only longer period of time Howard spent in a big city environment was in early 1919 when his family had to stay for seven weeks in New Orleans where Dr. Howard attended a supplemental course for his medical practice (Finn, 49). Besides his first encounter with the Picts, this stay in New Orleans though would be a memorable one for the thirteen-year-old Howard. During this visit, a spate of grisly murders occurred, committed by a killer the local press was quick to name after the tool he used for his crimes: The Axe-Man (Finn 49). This murderer would be mentioned in several of Howard’s future horror (“Pigeons From Hell“) and Crime stories (“People of the Serpent“).

Howard didn’t sell any detective stories in 1935, but in 1936 Kline sold two to Thrilling Mystery (“Graveyard Rats,” written in 1935″ and “Black Wind Blowing,” written between January and April 1936). This helped to offset the effects of not being paid by his primary market, Weird Tales magazine. Although Howard didn’t seem to mind at first that his payments were coming extremely late, this attitude changed when his mother’s health steadily worsened. Medical expenses that needed to be covered skyrocketed and in a heartbreaking letter, written in May 1935 (Collected Letters 3, 306) Howard literally begged Weird Tales’ editor Farnsworth Wright to pay him at least a fraction of the outstanding $800 the magazine owed him.

This brings us to our final question: Are Howard’s crime stories really as bad as their author’s critique makes them out to be?

Regarded strictly from a business perspective, it is difficult to say that Howard’s self-assessment of being unsuccessful was correct: If one considers Howard’s ‘real’ detective stories (those ones coming somehow close to as the genre is defined in literary dictionaries), the result would be that six out of nine stories were sold. This is certainly not a bad cut.

On the other hand, if one very generously combined these same stories with those described as ‘weird menace’ (crime stories in the broadest meaning featuring fantastic or supernatural elements) one will have a corpus of 21 stories. Here the result looks drastically different: Out of these 21, only six were published during Howard’s lifetime. Considering the time and effort it must have taken Howard to write them, such low sales numbers would justify his harsh self-criticism.

Low sales numbers though are not necessarily the best criteria in evaluating a lack of quality (as well as high sales numbers also do not necessarily mean ‘quality’…).

So, where does this leave us with our assessment of Howard’s skill when it comes to writing crime stories? Readers hoping to find regular crime stories in the style of hard-boiled classics like Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade novels or his Continental Op stories will without doubt be disappointed. The same applies to those readers expecting British school detective stories featuring characters such as Mrs. Marple, Hercule Poirot or Sherlock Holmes.

Howard certainly did not reinvent, redefine or add anything new to the crime stories genre, but he definitely put his very own spin on it. Howard’s stories are quite different from the ‘whodunit’ formula the genre is famous and popular for. The mystery or mysterious incident which is the catalyst of a regular crime story, and whose solution is central to the crime story is in Howard’s stories mostly incidental and acts more as a starting point for a series of action scenes executed in a tense atmosphere more typical of horror.

Although Howard’s crime stories are not on the same (artistic) level as others he is famous for, this does not mean that they are of inferior quality. They stand out as the attempts of a young writer trying to break into a new market by experimenting with a genre, he was unfamiliar with. The results are mostly well-written, entertaining (crime) stories with a heavy touch of REH personality. This touch is exactly the reason that they do not quite fit into the framework of how the crime genre defines itself. And in all honesty – isn’t that what we would expect from our favorite writer from Cross Plains, Texas and why we enjoy his work so much?

More information and footnotes

Footnotes:

1 “Brock Rollins” was originally Steve Harrison. It was a name the editors of Strange Detective Stories came up with when in Strange Detective Stories Vol. 5 Number 3 (1934) two Harrison stories were published in the same issue.

References:

- Assault on Precinct 13. Dir. John Carpenter. Screenplay by John Carpenter. Perf. Darwin Johnston, Austin Stoker. Assault on Precinct 13 (Collector’s Edition). Shout! Factory!, 2103. Bluray.

- Hammett, Dashiell. “The Maltese Falcon” Premium Collection. Timeless Wisdom Collection, 2014. Kindle AZW file.

- − − −. “Arson Plus” Premium Collection. Timeless Wisdom Collection, 2014. Kindle AZW file.

- − − −. “Slippery Fingers” Premium Collection. Timeless Wisdom Collection, 2014. Kindle AZW file.

- − − −. “Crooked Souls” Premium Collection. Timeless Wisdom Collection, 2014. Kindle AZW file.

- − − −. “Bodies Piled Up (House Dick)” Premium Collection. Timeless Wisdom Collection, 2014. Kindle AZW file.

- Cuddon, J. A., Preston, C. E. (revised edititon), eds. Dictionary of Literary Terms & Literary Theory. London: Penguin Books, 1999. Print.

- Finn, Mark. Blood & Thunder – The Life and Art of Robert E. Howard. 2nd ed. Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2011. Print.

- Goulart, Ron. Cheap Thrills. Hermes Press, 2007. Print.

- Howard, Robert Ervin. “The God in the Bowl.” The Coming of Conan of Cimmeria. Eds. Burke, Rusty, Louinet, Patrice. DelRey, 2003. Print.

- − − −. “The Tower of the Elephant.” The Coming of Conan of Cimmeria. Eds. Burke, Rusty, Louinet, Patrice. DelRey, 2003. Print.

- − − −. “The Black Moon.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “Graveyard Rats.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “The House of Suspicion.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “Lord of the Dead.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “Names in the Black Book.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “The People of the Serpent.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “The Silver Heel.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “The Tomb’s Secret.” The Exotic Writings of Robert E. Howard. Ed. Mechem, Neil. Girasol, 2006. Print

- − − −. “The Teeth of Doom.” Steve Harrison’s Casebook. Ed. Rob Roehm. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press, 2010. Print.

- − − −. “Pigeons From Hell.” The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard. Ed. Rusty Burke. Subterranean Press Press, 2010. Print.

- Joshi, S. T., Burke, Rusty, Schultz, David E., eds. A Means to Freedom – The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard: 1930-1932. New York: Hippocampus Press. 2011. Print.

- Joshi, S. T., Burke, Rusty, Schultz, David E., eds. A Means to Freedom – The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard: 1933-1936. New York: Hippocampus Press. 2011. Print.

- Roehm, Rob, ed. The Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard. Volume 1: 1923 – 1929. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press. 2007. Print.

- Roehm, Rob, ed. The Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard. Volume 3: 1930 – 1932. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press. 2007. Print.

- Roehm, Rob, ed. The Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard. Volume 3: 1933 – 1936. The Robert E. Howard Foundation Press. 2007. Print.

Article written by Dierk Günther, Ph. D. Gakushuin Women’s College, Tokyo/Japan.

This entry was posted on January 1, 2016 on the REH: Two-Gun Raconteur blog as “Gumshoes, Gats and Gals: Robert E. Howard’s Detective and Crime Stories”

Posted September 8, 2022. Layout changed, additional images and links added by Ståle Gismervik.

Teaser image by: Guillaume Sorel.